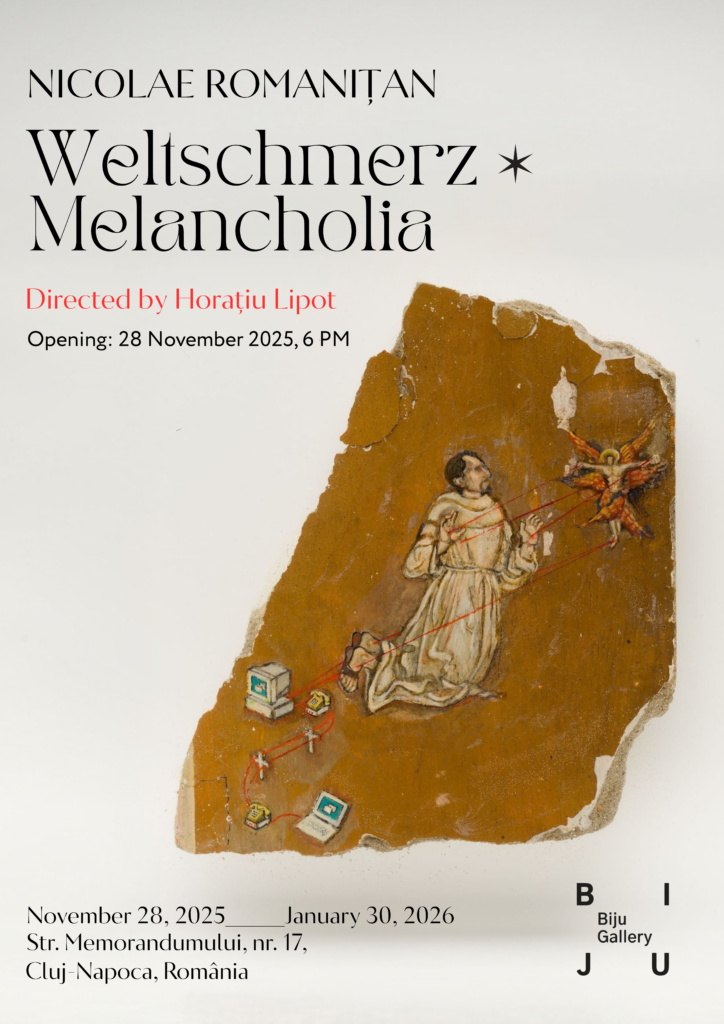

Welschmerz Melancholia to Nicolae Romanitan

There is an obscure school of thought that claims that the individuals who still experienced childhood in the early 2000s, those who grew up within the atmosphere of the great societal narratives, not yet shaken by the deconstructivism that overturned the logocentric order –individuals raised with the archaic tales of fairy stories, with the eternal battles between good and evil in the first video games, pre-Sims, raised within the moralizing camouflage of American soap opera TV productions; individuals who saw millenarianism in episodes like the Y2K error or the year 2012 – these are the ones who might represent the last children of antiquity.

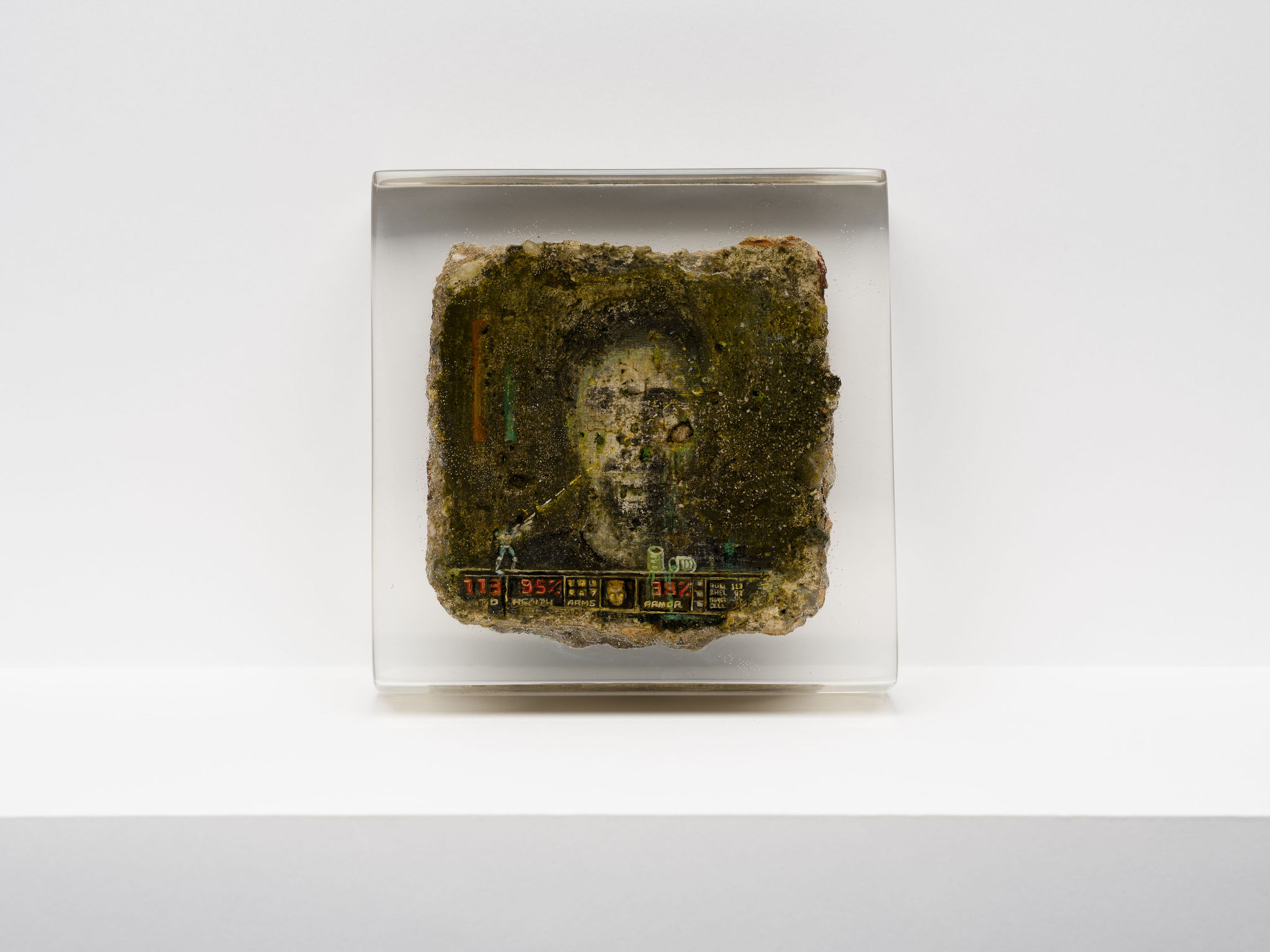

Let us now transport ourselves to Cugir city in the year 2000, the town where the artist Nicolae Romanitan grew up, and which is defining, as we shall see, for shaping the extra-personal iconography in his paintings. We speak of a regional, industrial town which, for more than two centuries, has been one of the historical centers of metallurgical processing in the region. A town that is 90% armor, like in one of the artist’s panel paintings. The factory there is not only an economic and urban symbol, but a collective identity for a community that has long identified itself with various legends, more or less fantastical, centered around this factory and its later function, as production of weaponry. Today, it is part of ROMARM and produces NATO ammunition, pistols, and weapon components.

In such small towns, the only real pastime and meeting place for children and teenagers of this times were the terraces serving TEC sodas and the arcade gaming halls, later replaced by Playstation console rooms. In 1990s Romania, these halls were, in fact, the only America available , filtered through the cracks of the transition period. There were no McDonald’s or malls in such towns –there still aren’t any – and the internet appeared timidly, still in the era of the small neighborhood providers. Yet there were Terminator 2, Cadillacs & Dinosaurs, Street Fighter, white and red buttons, and bulging cathode monitors set at 45-degree angles. Later, by the late ’90s and the beginning of the 2000s, many arcades lost ground to LAN cafés (networked PCs) and to rooms equipped with consoles. Home consoles were still under the proto-digital aesthetic of the arcade, supplied by the markets found in every small regional town under 20,000 inhabitants. More than America, the arcades were also the first contact a generation had with the digital world – even if only with its aesthetics, and not yet its functionality. In the ’90s, childhood inside a gaming hall was a kind of initiatory act, profoundly urban. It was a form of socializing in unmixed 8-bit neon colors.

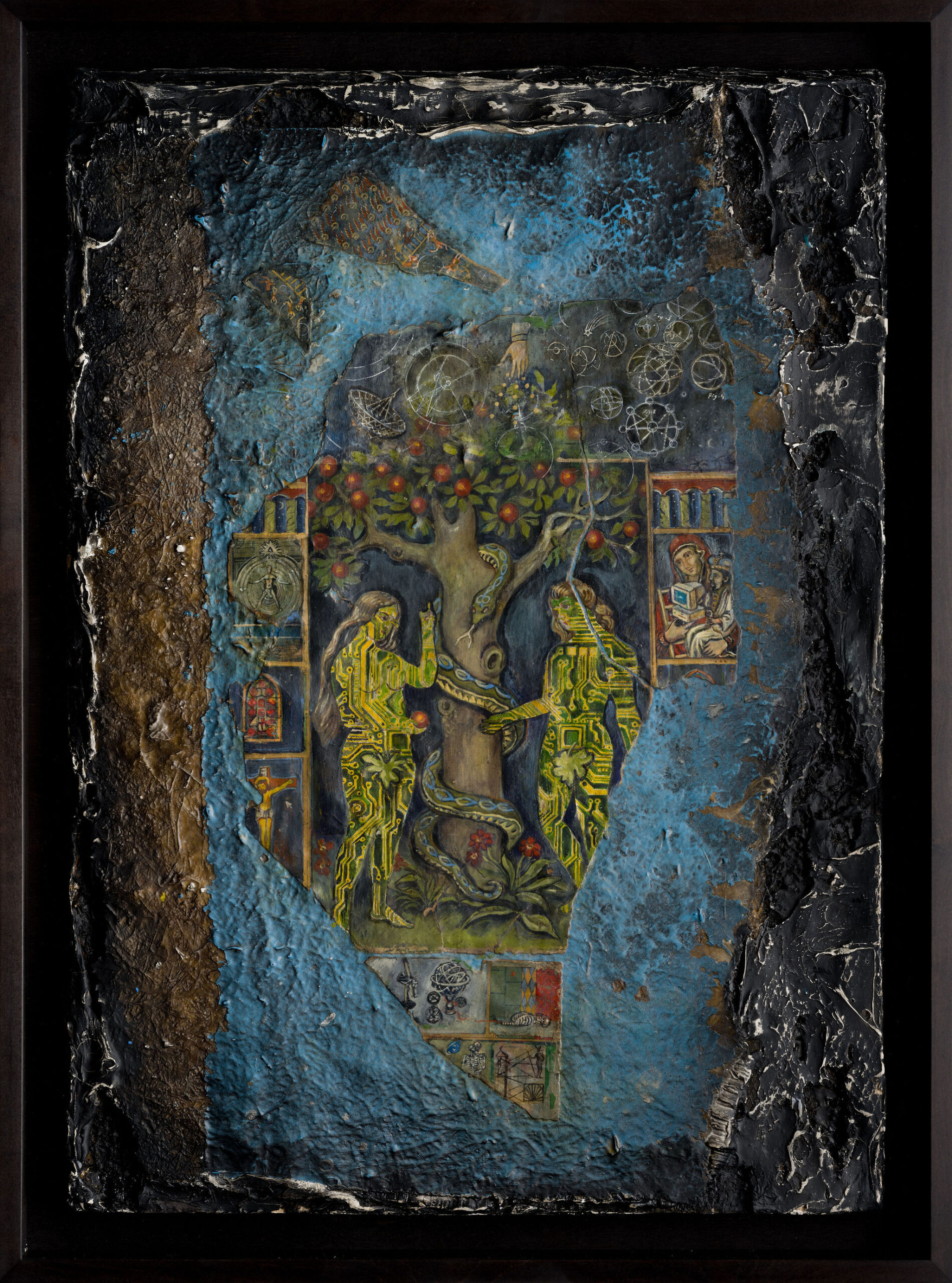

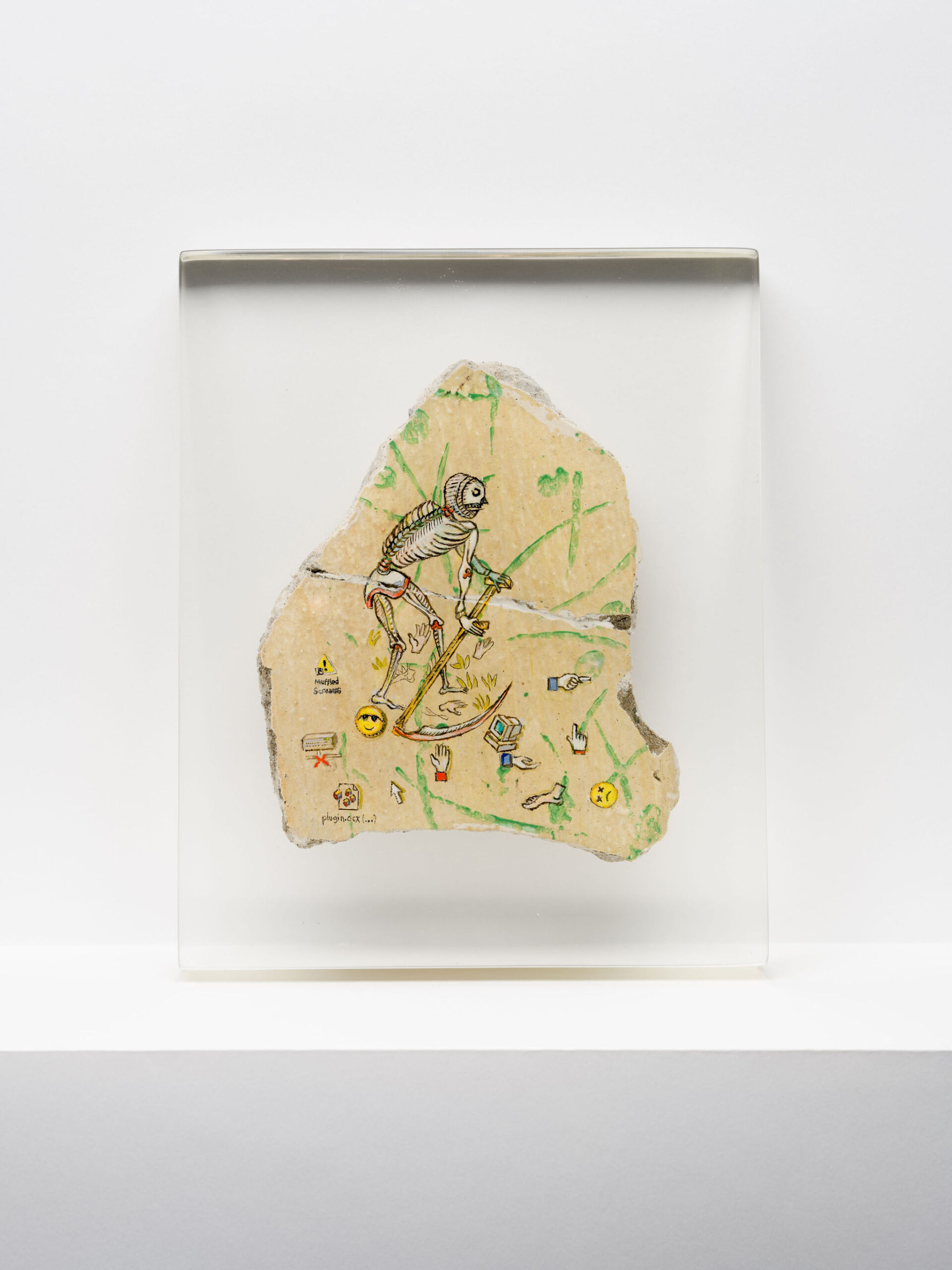

As we can see in the relic-like scenes of NR, games such as Minesweeper, The Lost Vikings, Doom 2, Mortal Kombat can function as a mythology comparable to any other from antiquity or from various religions. It is the aesthetic of the games played on the computers in informatics classrooms , thos rooms with smell of petrol – at a time when most people did not yet own a personal computer. Today, NR owns both a computer and a Playstation, and it is relevant to mention, for understanding the context of his works, that the console is placed in his studio, opposite the workbench.

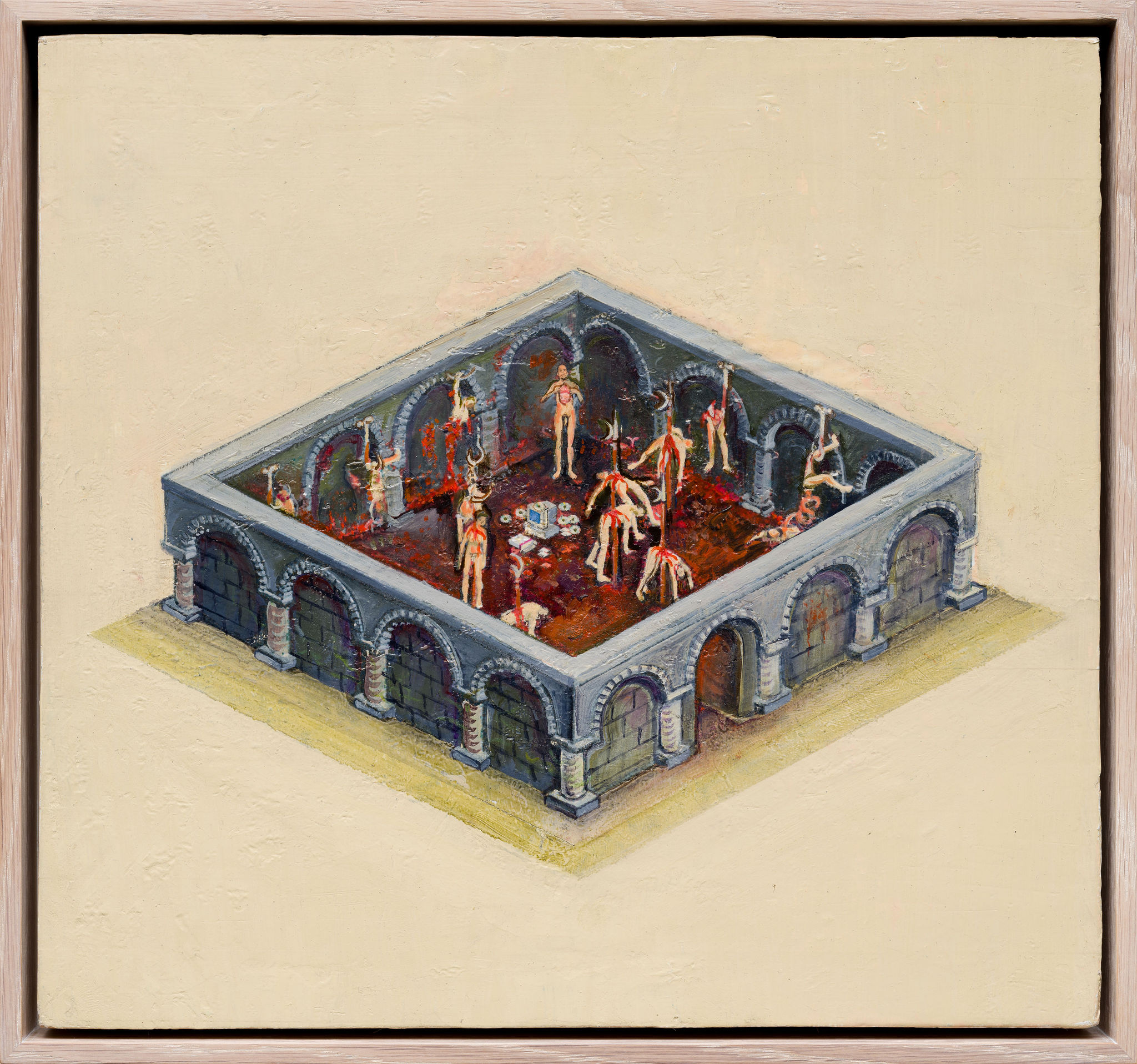

Yet these are not mere appropriations of images. They encode within them a thesis of technological determinism, in which the body is always objectified, subjected to attacks from hardware-type artefacts, not from those based on AI and software.

If this is one clear source of the imagery in NR’s works, the other source that interferes with this imaginary is rooted in the history of pictorial tradition, narrative structure, and illusionism. We can observe a preference for compositional treatments specific to Byzantine or Gothic art: a claustral spatiality, with a narrow perspectival depth in which that historia can unfold. At other times, the scenes evoke a comic-moralizing spirit typical of Flemish art. It is worth noting that NR is not an isolated case; within much of his generation – especially those trained in Cluj and focused on the canonical representational genres such as painting and drawing – there is a tendency toward imagery taken from classical iconographies: Egyptian, Roman, or Byzantine.

Within these narrative scenes, there exists a pleasure, a vitalist eros, explicitly associated with death. As we easily observe, the themes always gravitate toward apocalypse, whether personal, or political, through depictions of historical episodes such as the Doomsday Clock. On this imaginary clock, midnight represents a critical point: nuclear war, climate collapse, or other major threats. Furthermore, the very designation of the recovered wall fragments, treated in oil as relics, accentuates their material character as survivors of a global and total cataclysm.

Regarding the intimate, personal body, itself headed toward its own form of apocalypse, it is always engaged in battle or attacked by something external, often invisible, whose presence we perceive only through its weapons, almost exclusively memory-storage devices like CDs or USBs. We see the artist’s self-portrait weighed/judged, attacked, or emerging triumphant. I cannot help but see here a biographical parallel with the way Nicolae Romanitan’s image has often been instrumentalized, extra-artistically, within the artistic scene –focusing on his personality rather than his works. Visually, this also carries the characterological substrate of the ancestral trickster: the one who, under the appearance of a social pariah, transcends all secrets and successive courts, only to become the grey eminence who knows everything without being observed. Why do the bells toll, Mitică? — for the rope, mate. Let us call it Visionary & Victimar Realism.

Last, I must also tell the story of Borges’ Map. It refers to a philosophical and metaphorical concept about representation, derived from the short story “On Exactitude in Science,” included in A Universal History of Infamy. Borges recounts a dynasty in which cartographers created a map so exact that it was the size of the empire itself. The map covered the territory 1:1, point by point, becoming impossible to use — useless. Later generations abandoned it, and its fragments were left to decay in the desert. Such, it seems, are the extra-biographical fragments of NR, now recovered within the exhibition space.

Weltschmerz Melancholia lui Nicolae Romanițan

Există o obscură școală de gândire care postulează că indivizii care au mai prins copilăria la începutul anilor 2000, cei care au crescut în ambianța marilor narațiuni societale, nezdruncinate încă de deconstructivismul răsturnării ordinii logocentrice – indivizi formați cu narațiunile arhaice ale basmelor, cu eternele lupte dintre bine și rău din primele jocuri video, ante Sims, crescuți în camuflajele moralizante din producțiile TV tip soap americane; indivizi care au văzut milenarism în episoade ca eroarea Y2K sau anul 2012 – sunt cei care ar reprezenta ultimii copii ai antichității.

Să ne transportăm acum în Cugirul anilor 2000, oraș în care artistul Nicolae Romanițan a crescut și care este definitoriu, cum vom vedea, în conturarea iconografiei extra-personale din picturile sale. Vorbim de un oraș tip regional, industrial, care de mai bine de două secole a fost unul dintre centrele istorice ale prelucrării metalurgice. Oraș cu 90% armor, ca într-o pictură pe panou a artistului. Uzina de acolo nu este doar un simbol economic și urbanistic, ci o identitate colectivă a unei comunități care s-a identificat cu tot felul de legende, mai mult sau mai puțin fanteziste, având în centru această fabrică și producția sa ulterioară, cea de armament. Actual, aceasta este parte din ROMARM și produce muniție NATO, pistoale și componente de arme.

În asemenea orașe mici, cam unica distracție și loc de întâlnire pentru copiii și adolescenții anilor de cumpănă 2000 erau terasele cu sucuri TEC și sălile de jocuri tip arcade, înlocuite mai apoi de cele cu console Playstation. În România anilor ’90, aceste săli reprezentau, de fapt, unica Americă, filtrată prin crăpăturile tranziției. Nu existau în astfel de orașe – nu există nici acum – McDonald’s sau mall-uri, internetul apărea timid, fiind încă în epoca furnizorilor de cartier; însă existau Terminator 2, Cadillacs & Dinosaurs, Street Fighter, butoane albe și roșii și monitoare catodice bombate, așezate la unghiuri de 45°. Mai apoi, odată cu sfârșitul anilor ’90 și începutul lui 2000, multe din sălile arcade au pierdut teren în faţa LAN café-urilor (PC-uri în reţea) şi a celor dotate cu console – cele de acasă erau încă sub estetica proto-digitală, furnizată de piața de la ruși a fiecărui oraș tip regional sub 20.000 locuitori. Mai mult decât America, arcade-urile reprezentau primul contact al unei generații cu lumea digitală, fie și doar în estetica, nu în funcționalitatea ei. În anii ’90 și ’00, copilăria într-o sală de jocuri era un soi de act inițiatic, profund urban. Era o socializare în culori neon de 8-biți, neamestecate.

Cum vedem în scenele relicvelor lui NR, jocuri precum Minesweeper, The Lost Vikings, Doom 2, Mortal Kombat pot constitui o mitologie similară oricărei alteia din antichitate sau din diverse religii. O estetică a jocurilor de pe computerele de la ora de informatică din sălile curățate cu petrol, când majoritatea populației încă nu deținea un PC personal. Astăzi, NR deține atât computer, cât și Playstation, iar în contextul lucrărilor este relevant că acesta este amplasat în atelier, opus bancului de lucru.

Însă acestea nu sunt simple preluări de imagini, ci au încifrată în ele o teză a unui determinism tehnologic, în care corpul este mereu obiectificat, supus atacurilor artefactelor de tip hardware, nu celor bazate pe IA și software.

Dacă aceasta este o sursă clară a imaginilor din operele lui NR, cealaltă sursă care interferează cu acest imaginar are la bază istoria tradiției picturale, a narativității și iluzionismului. Se observă o preferință pentru tratarea compozițională specifică artei bizantine sau gotice: o spațialitate claustrantă, cu un spațiu perspectival îngust, în care acea historia se desfășoară. Alteori, scenele evocă un spirit comic-moralist tipic artei flamande. Aici trebuie menționat că NR nu este un caz izolat; se observă în bună parte a generației sale – în special cea formată la Cluj și axată pe genurile clasice ale reprezentării precum pictura și desenul – o tendință pentru imaginea preluată din iconografii clasice, fie ele egiptene, romane sau bizantine.

Există în aceste scene narative o plăcere, un eros vitalist, asociat explicit cu moartea. Cum lesne observăm, temele țin mereu de apocalipsă, fie una personală, fie una în cheie politică, prin redarea unor episoade istorice ca Doomsday Clock (Ceasul Apocalipsei). În acest ceas imaginar, miezul nopții reprezintă un punct critic, războiul nuclear, colapsul climatic sau alte din pericole majore. Mai mult, chiar această denumire a fragmentelor parietale recuperate și tratate în ulei ca relicve, le accentuează un anume caracter material, ca de supraviețuitoare ale unui cataclism global, total.

În ceea ce privește corpul intim, personal, și el îndreptat spre o apocalipsă proprie, acesta apare mereu angajat în luptă sau atacat de ceva extern, adesea invizibil, al cărui impact îl intuim doar prin armele sale – aproape exclusiv dispozitive de stocare a memoriei, precum CD-uri, carduri de memorie sau USB-uri. Vedem autoportretul artistului ba cântărit/judecat, ba agresat, ba ieșind triumfal și iconic-victorios. Nu pot să nu văd aici o paralelă biografică cu felul în care imaginea lui Nicolae Romanițan a fost de multe ori instrumentalizată, extra-artistic, în zona personalității sale și mai puțin a lucrărilor, de către scena artistică. Imagistic, aceasta comportă și un substrat caracteriologic al figurii bufonului/ancestralului trickster, cel care, sub aparența unui paria social, transcende toate secretele și succesivele curți, doar pentru a se erija în acea eminență cenușie care știe totul fără a fi observat. De ce trag clopotele, Mitică? – de funie, bă. Să-i spunem Realism Vizionar & Victimar.

În încheiere, trebuie să spun și povestea Hărții lui Borges. Aceasta se referă la un concept filozofic şi metaforic despre reprezentare, derivat din povestirea „Despre rigoare în știință”, inclusă în Istoria universală a infamiei. Borges relatează despre o dinastie în care cartografii au creat o hartă atât de exactă încât avea dimensiunea imperiului însuși. Harta acoperea teritoriul 1:1, punct cu punct, devenind imposibil de utilizat, inutilă. Generațiile următoare au abandonat-o, iar fragmentele ei au rămas să se destrame prin deșert – cam așa par și fragmentele extra & meta biografice ale lui NR, iată, recuperate acum în cadru expozițional.

Horațiu Lipot