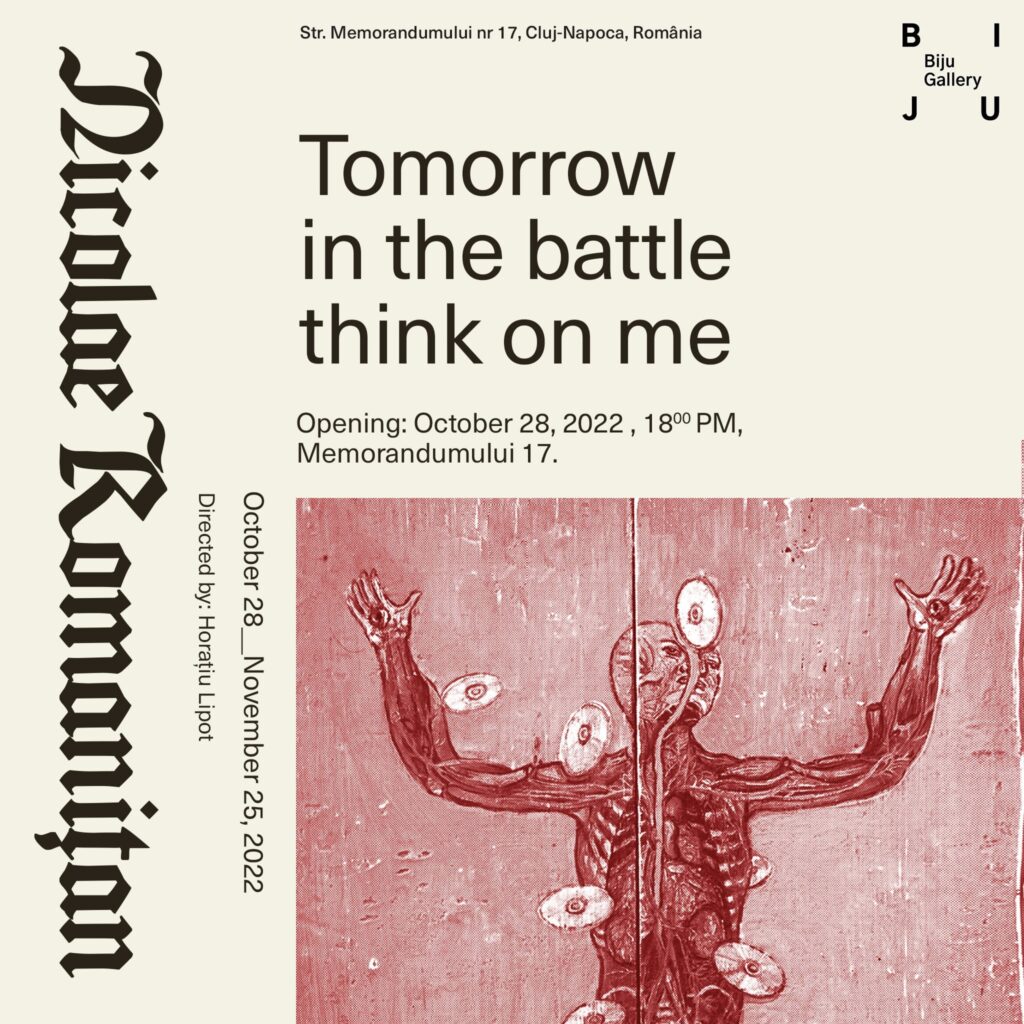

Tomorrow in the Battle Think on Me

“and fall thy edgeless sword” are the words with which obsessively like in a baroque ritornello, a suite of ghosts contaminate the dreams to Richard III, dooming him in the battlefield like something from the past that is meant to block your evolution. Speculatively & psychologically, ghosts are incomplete acts that take shape from a rumor, from a past not yet fully recovered and assumed, from envy, from the naivety of the one who overlooks them, from everything that we collectively let fill a void that gets progressively darker with each exponential growth. “Tomorrow in the battle think on me” is also an incantation that follows the narrator of the eponymous novel by Javier Marias, an anaphora relentlessly unfolding a predetermined scenario in which the decisive moments of the actant are guided from outside, himself remaining peripheral to the action in which is subjected and that he nevertheless influences, as observer, actor, witness and main character. Through this metaphor of past ghosts, the author constructs a discourse about the time spent living under false impressions, examining how those who are unaware of events act differently through their lack of knowledge, behaving in a way they would not have if they had access to the all the objective facts.

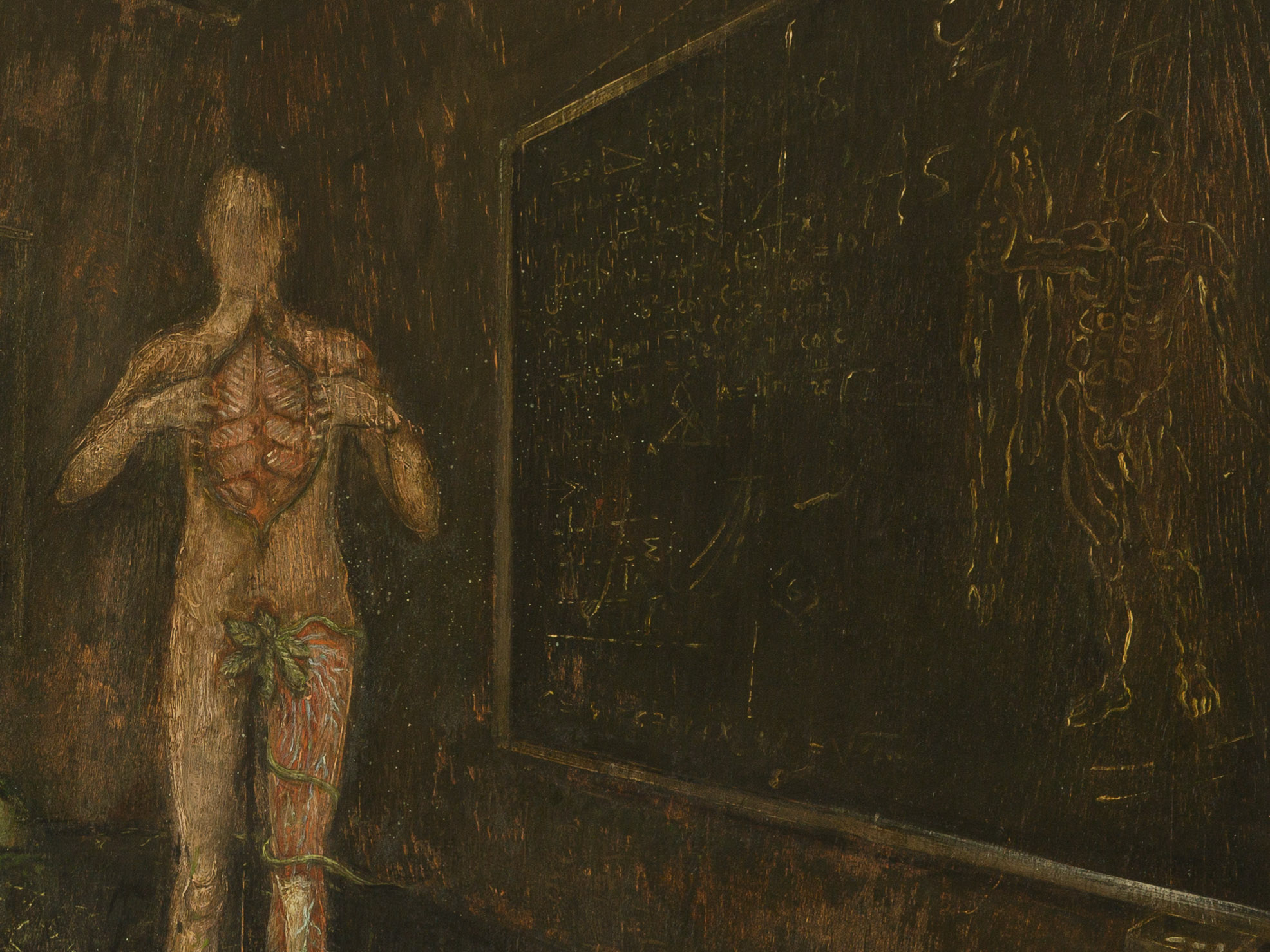

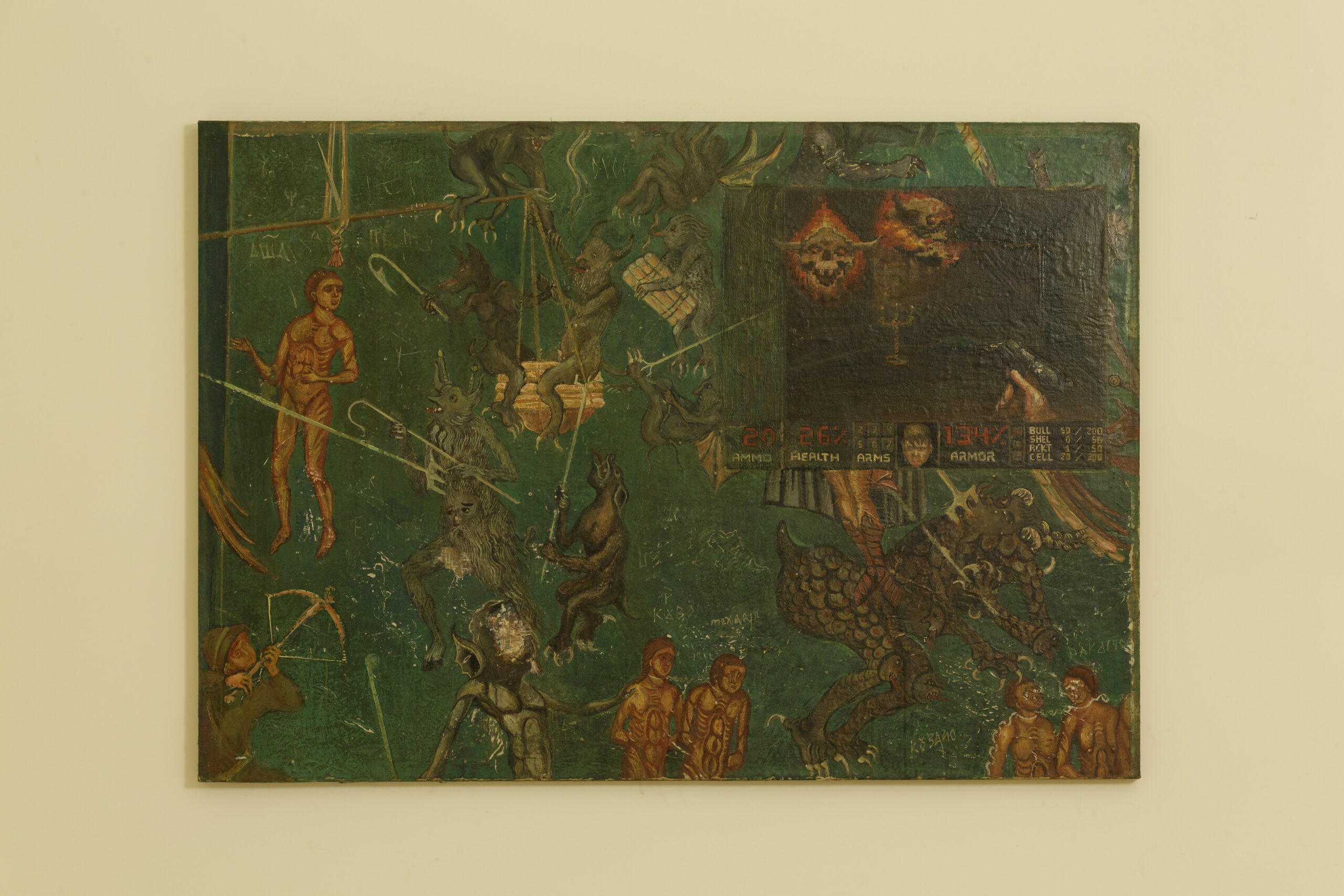

As a whole, the corpus of works created in the last 2 years by Nicolae Romanitan highlights two apparently distinct directions: within a composition inspired by the Gothic tradition of the Quattrocento – rather than the Renaissance one- are unfolding invasive scenes of humanoid characters, in a world where the technological singularity is on the verge of happening. With a strange verisimilitude, as kind of a narrative uncanny valley specific to magical realism, where the artist’s compositions seem like the frescoes of an authentic techno-vernacular civilization, like those from “Ancient Aliens” series, broadcast on the historic documentary TV channels.

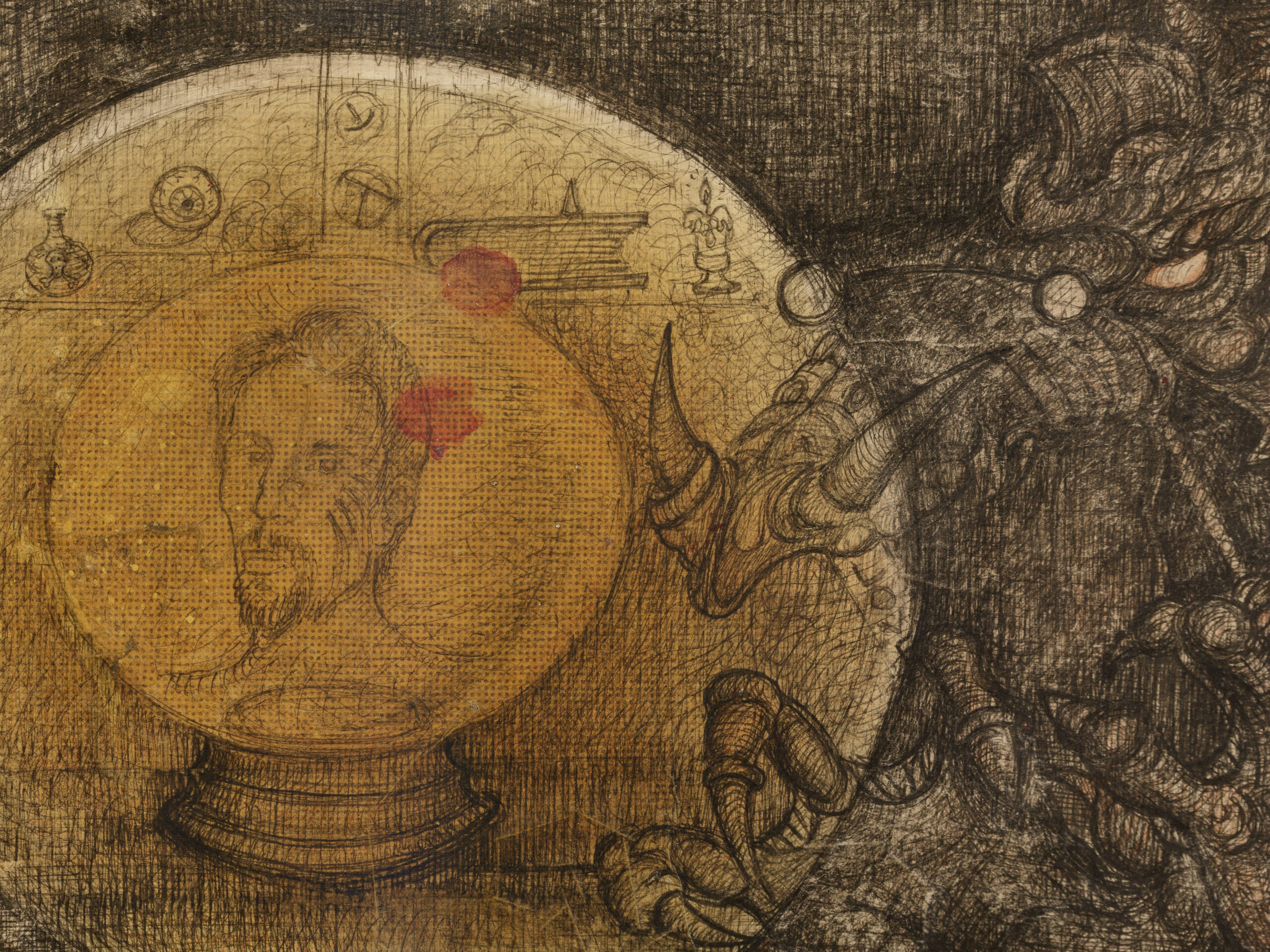

Often depicted episodically, borrowing both from the 90s video game aesthetics and Byzantine iconography – such as the type of synaxarion-like rendering of scenes in dials – the ubiquitous nocturnal atmosphere is not one of a natural setting, but a claustrophobic panopticon as that of a dimly lit room, only with a relentless neon above the “interview” chair. Often combined with a deliberate precariousness of the support or of materials and techniques used, the works can be contained in a certain aesthetic typology specific in recent years to the center and east of Europe driven by platforms like Tzvetnik or Ofluxo, which has as its starting point the New Black Romanticism, with an appearance typical of a stronghold interior – directly from its basement and torture chamber – where the body seems to be subjected to the new technological tools, yielding, descending, laying down. It is perhaps in the insistence of these perishable instances, hidden an intrinsic will that by destroying materiality the transition to the fully digital will be easier to make.

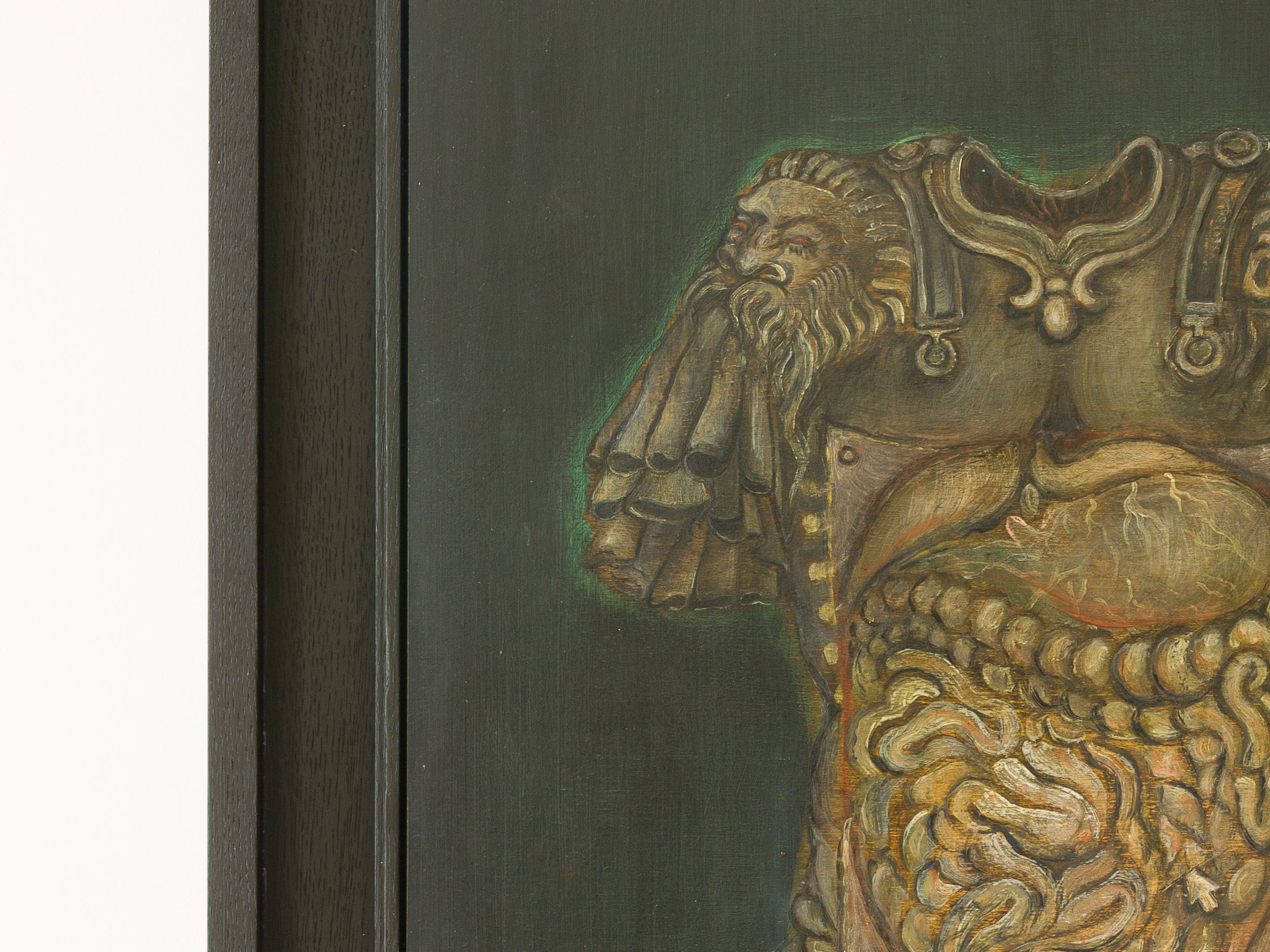

However, when occurring, the interactions of Nicolae Romanitan’s characters with technology are not pacifist or collaborative, involving, say, the exchange of information or the probing of a Turing test – it does not happen in “software” but in the “hardware” area, this being more than often implanted by force, and surgically placed into the body, in a space that seems an improvised garage lab. They are like the classical scenario with the last remnants of the planet in a sci-fi movie, improvising humanoid machines, building hastily and precariously. It is Millenarianism repeated in full digital age. We are not talking here about precise operations that connect the optical fiber cables perfectly on the aorta, but rather crude adhesions, so that the area signals the inflamed foreign body of the parasite that is about to receive its host. They are the last spasms of an obsolete body in the face of new materiality, building in haste, using all organic textures in hope of keeping what is disappearing.

Another obvious practice/effect that the artist relies on is multiplicity. Emphasized by the repetition of the same subject in different contexts, Nicolae Romanitan uses through this the very basic principle of the production system that is at the origin of the post-industrial world. Once again, through the chosen method of pointing out an excess, the artist manages to solve more effectively than through criticism, highlighting what is wrong with the “body” chosen for study and dissection. Of course, the one who showed, was the one punished for it – as St. Sebastian – which is a recurring motif in the artist’s works.

The tools that all these representations have on hand are blunt or defensive ones. Fantastic anthropomorphic animals hunted down by medieval soldiers look more in melancholy than menacing at their oppressors, with the consciousness of extinction but also of exoticism in their eyes. They are the representations of the artist, or of the typology of the “artist” from which Nicolae Romanitan claims himself, and how they are seen today. Because in this universe that preconfigures precisely through exacerbations the way in which the body, more than the mind, directly feels all these transitions of the current world, many of the works write their matrix from a code based on biographical experiences that encode within them harsh existential events. These belong either to a social structure seen as changing, or to clashes that are representative to typologies specific of an extra-competitive formative artistic environment, or to the realities of a still small town let’s be honest, from a country in Eastern Europe. They are parables about old exorcisms that today become public trials, about excommunications that tend to became social isolations, that when spoken about, being so current and alive, for the time being the favorite formula of jurists must be used: I’m asking for a friend.

Horatiu Lipot